The Islamicity Foundation’s 2017 Annual Report

Building Effective Institutions for Political, Social and Economic Reform and Progress

Download the PDF version of this report

1. Executive Summary

The Islamicity Indices are made up of five indices, namely, the Economic (EI), Legal and Governance (LGI), Human and Political Rights (HPRI), International Relations (IRI) and the cumulative Overall (OI). In the 2017 index notable improvements in terms of scores were made by the Dominican Republic (EI), Togo (LGI), Niger (HPRI), Libya (IRI) and Honduras (OI). Syria’s scores declined the most across all the indices.

The self-proclaimed Muslim countries performed lower than the global average on OI relative to 2016. They made significant declines in their scores on EI and IRI. Their average scores on HPRI also declined. While the world average improved, the Muslim average declined. Only on LGI did the Muslim countries improve significantly. However, when looking at the score, it becomes evident that these countries had a much lower average to begin with, which was thus easier to improve upon. Among the Muslim countries, Malaysia had the highest score on EI and OI, the United Arab Emirates on LGI and Albania on HPRI and IRI. At the other end, Yemen had the lowest score on EI, HPRI, and OI, Libya on LGI and Syria on IRI.

The results demonstrate that the majority of the Muslim countries fell in the lower half of the indices. Particularly noteworthy is their concentration in the lowest quartile in terms of both rank and score. Joining them in the two lower quartiles are largely sub-Saharan African and Eastern European countries.

The Islamicity Indices 2017 results are analyzed in greater detail in this report. The findings are followed by developments in the Islamicity Foundation, its Board of Advisors, and in its Board of Directors, followed by details of our Country Partners in the appendix.

2. Broad Developments During the Year

Sound and efficient institutions are widely accepted to be an essential pillar, if not the very foundation, of a country’s economic and social development and growth. Effective institution building, as recognized by Douglass North and others, takes much time. The condition of countries that suffer from weak institutions is path dependent and has been the result of centuries, or at least many decades, of missed opportunities and unhelpful policies and practices. These conditions are typical of the majority of Muslim countries. The institutional scaffolding that is recommended in Islam and is similar to the structure envisaged by Adam Smith[1] to build strong and robust institutions for the service of citizenry requires a much higher degree of morality and justice than is the case in Muslim-majority countries.

How can this turnaround in Muslim countries be initiated, developed and sustained? The Islamicity Indices premise that peaceful and positive change in Muslim countries will have to come about in the context of Islam. For this turnaround, Muslims would have to better understand Qur’anic teachings and strive to establish effective institutions based on the Qur’an and the hadiths to replace their weak institutions and retrograde economies.

The Islamicity Indices provide the compass and the basis for establishing effective institutions, restoring hope, achieving sustainable development and for strengthening global order. These indices serve as an indication of the degree of compliance with Islamic teachings as reflected in the Islamic landscape of a community.

The Indices provide a tool for the people and their supportive rulers to ensure that their government’s policies adhere to the teachings of the holy book and prescriptions of the prophet surrounding economic opportunities, legal and governance affairs, human and political rights and international relations. Those four indices are, in turn, aggregated under an overall index that encompasses the other four. By adopting these indices, the population of a country are internalizing the teachings of the Qur’an and supporting peaceful reforms and effective institutions.

There are only seven declared Islamic countries (Afghanistan, Bahrain, Iran, Mauritania, Oman, Pakistan, Yemen) and only twelve countries that have declared Islam as the state religion (Algeria, Bangladesh, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, Maldives, Morocco, Qatar, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates). In developing the Islamicity Index we have chosen an all-encompassing approach which is to include all countries whose governments profess Islamic teaching as the guiding, or one of the primary, principle for governance. To this end, we decided that the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) provides a good representation of countries that profess Islam at the national level. While the OIC has a membership of 57 states, we have the needed data for 39 member countries that have either:

- governments that have adopted Islam as the official state religion, or

- Islam as their primary religion, or

- a significant Muslim population, or

- simply declared themselves an Islamic republic.[2]

“How Islamic are Islamic countries or what is their degree of “Islamicity”? We, therefore, attempt to discern if Islamic principles are conducive to (a) free markets and strong economic performance, (b) good government governance and rule of law, (c) societies with well-formed human and civil rights and equality and (d) cordial relations and meaningful contributions to the global community, or are they, in fact, a deterrent. In the Islamicity Index we look at 152 countries and compare them to a subset of the OIC countries. We attempt to measure the economic, social, legal and political development of OIC countries, not only by Western standards, well documented in various well-known index rankings,[3] but by what we believe to be Islamic standards.

2.1 Overall Index Changes in Country Scores

This year’s Indices highlight that the majority of countries are making little to no progress on improving their Islamicity scores.[4] The Index, which ranks 152 countries by their economic, legal and governance, human and political rights, international relations as well as their overall Islamicity, uses a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is highly un-Islamic and 10 is highly Islamic. This year, the index found that out of 39 self-proclaimed Islamic countries, 32 had a score of less than 5 in overall Islamicity. The results demonstrate that the majority of Muslim countries fell in the lower half of the indices. Particularly noteworthy is their concentration in the lowest quartile in terms of both rank and score. Joining them in the two lower quartiles are largely sub-Saharan African and Eastern European countries.

Table 1: Median Islamicity Scores in 2017

| Description | OI | EI | LGI | HPRI | IRI |

| All Countries | 4.63 | 4.72 | 4.70 | 4.8 | 4.95 |

| Muslim Countries | 3.13 | 3.80 | 2.79 | 3.11 | 3.65 |

| Non-Muslim Countries | 5.54 | 5.35 | 5.56 | 5.75 | 5.40 |

| Percentage Change Relative to 2016 for All Countries | -2.97% | 1.59% | 0.80% | 3.06% | 0.35% |

| Percentage Change Relative to 2016 for Muslim Countries | -1.81% | -8.41% | 7.12% | -2.34% | -5.57% |

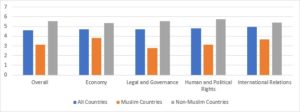

In 2017, the median overall score for all Muslim countries was 3.13. The world average stood at 4.63. The score for Muslim countries decreased by 1.18% relative to 2016. The trend is true for all the studied countries; the world average decreased by 2.97% compared to the previous year. When similarly separating out all the non-Muslim countries, we see that they fared significantly better with an average overall score of approximately 5.54. The results show that Muslim countries accounted for the lowering of the world average.

The economic score saw an improvement for the world average. It improved by approximately 1.6%. For the Muslim countries, the average economic score saw a deterioration of 8.41%. The same correlation applies to human and political rights as well as international relations. While the world average improved, the Muslim average declined. The largest variation was in the economy, followed by human and political rights.

Only in legal and governance did the Muslim countries improve significantly. However, when looking at the score, it becomes evident that these countries had a much lower average to begin with, which was thus easier to improve upon. The Muslim countries’ average score in 2017 was 2.79, relative to the non-Muslim average of 5.56. Non-Muslim countries fared almost twice as well, which helped bring the world average to 4.70.

Figure 1: Median Islamicity Scores in 2017 On the whole, Muslim countries regressed in their economic, human and political rights, international relations and overall score. In the absence of any global or regional financial crisis or major conflicts, their mediocre performance is largely attributable to poor policies and lack of reform. Analogously, these countries also suffer from public and private, grand and petty forms of corruption that hinder their development and implementation of reform policies, if they were to adopt them.

On the whole, Muslim countries regressed in their economic, human and political rights, international relations and overall score. In the absence of any global or regional financial crisis or major conflicts, their mediocre performance is largely attributable to poor policies and lack of reform. Analogously, these countries also suffer from public and private, grand and petty forms of corruption that hinder their development and implementation of reform policies, if they were to adopt them.

2.2 Countries with Significant Improvement and Decline in Overall Index Score

Countries that have had more than a 10% change in their overall index scores relative to the previous year are classified as those with significant improvements and declines in 2017 relative to the previous year. Table 2 depicts those countries, their score changes and their ranking changes.

Honduras, Paraguay and Togo were among the top world performers, having increased their overall score by 15-20% within a year. All three countries have made significant improvements in one or more indices that saw their score inch closer to and even surpass the global median. Major declines were seen in Syria, Iraq and Libya. The reason for their decline is self-evident. All three countries are suffering from internal strife, instability and rampant corruption. Syria continues to be a battlefield, while the Iraqi and Libyan governments have struggled to create stability and unity in their divided countries.

Table 2: Significant Improvements and Declines in Overall Index Scores

| Country | 2017 OI | 2016 OI | % Change in Score | ||

| Rank | Score | Rank | Score | ||

| Syrian Arab Republic | 144 | 2.18 | 136 | 2.78 | -21.58% |

| Iraq | 141 | 2.41 | 131 | 2.81 | -14.23% |

| Libya | 136 | 2.57 | 123 | 2.98 | -13.76% |

| Saudi Arabia | 88 | 4.4 | 67 | 4.97 | -11.47% |

| Ethiopia | 135 | 2.59 | 127 | 2.91 | -11.00% |

| Sri Lanka | 85 | 4.41 | 68 | 4.93 | -10.55% |

| Gabon | 122 | 3.13 | 113 | 3.49 | -10.32% |

| Mali | 123 | 3.09 | 132 | 2.8 | 10.36% |

| Dominican Republic | 60 | 5.16 | 78 | 4.67 | 10.49% |

| Niger | 116 | 3.27 | 125 | 2.93 | 11.60% |

| Belize | 72 | 4.79 | 85 | 4.29 | 11.66% |

| Burkina Faso | 100 | 3.9 | 114 | 3.47 | 12.39% |

| Armenia | 80 | 4.51 | 90 | 3.99 | 13.03% |

| Togo | 118 | 3.23 | 133 | 2.8 | 15.36% |

| Paraguay | 84 | 4.46 | 98 | 3.79 | 17.68% |

| Honduras | 92 | 4.18 | 112 | 3.49 | 19.77% |

2.3 Countries with the Largest Overall Index Rank Improvements and Declines

Of the world countries with significant overall score changes, those with significant rank improvements include Honduras, the Dominican Republic and Togo with rank changes of 20, 18 and 15, respectively. Among the Muslim countries, it was Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. Having increased their scores by more than 10%, they have elevated their ranks from 114 to 100 for Burkina Faso, from 132 to 123 for Mali and from 125 to 116 for Niger.

Saudi Arabia, Libya and Iraq showed a big decline in their rankings. Saudi Arabia fared the worst with a decline of more than 20 (from 67 in 2016 to 88 in 2017). Libya was not far behind with a decline of 13 (from 123 to 136). Iraq decreased by 10 (from 131 to 141). While the reasons for Iraq and Libya remain instability and conflict, Saudi Arabia’s decline is largely attributable to the recent wave of reform policies adopted by its government, which have not had a positive impact on the Kingdom.

Table 3: Significant Improvements and Declines in Overall Index Ranks

| Country | 2017 OI | 2016 OI | Change in Rank | ||

| Rank | Score | Rank | Score | ||

| Honduras | 92 | 4.18 | 112 | 3.49 | 20 |

| Dominican Republic | 60 | 5.16 | 78 | 4.67 | 18 |

| Togo | 118 | 3.23 | 133 | 2.8 | 15 |

| Burkina Faso | 100 | 3.9 | 114 | 3.47 | 14 |

| Paraguay | 84 | 4.46 | 98 | 3.79 | 14 |

| Belize | 72 | 4.79 | 85 | 4.29 | 13 |

| Armenia | 80 | 4.51 | 90 | 3.99 | 10 |

| Mali | 123 | 3.09 | 132 | 2.8 | 9 |

| Niger | 116 | 3.27 | 125 | 2.93 | 9 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 144 | 2.18 | 136 | 2.78 | -8 |

| Ethiopia | 135 | 2.59 | 127 | 2.91 | -8 |

| Gabon | 122 | 3.13 | 113 | 3.49 | -9 |

| Iraq | 141 | 2.41 | 131 | 2.81 | -10 |

| Libya | 136 | 2.57 | 123 | 2.98 | -13 |

| Sri Lanka | 85 | 4.41 | 68 | 4.93 | -17 |

| Saudi Arabia | 88 | 4.4 | 67 | 4.97 | -21 |

2.4 Summary of Major Changes in the Five Indices

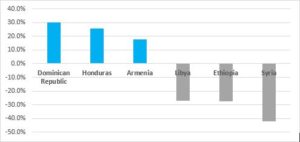

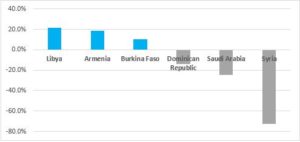

The Dominican Republic, Honduras and Armenia made the highest improvements on EI with increases of 30.0%, 25.6% and 17.6%, respectively. Similarly, their rank improved from 109 to 74 for the Dominican Republic, from 131 to 96 for Honduras and from 83 to 67 for Armenia. Notable declines were made by Syria (-42.2%), Ethiopia (-27.6%) and Libya (-26.9%), decreasing their ranking by 65, 27 and 18 respectively.

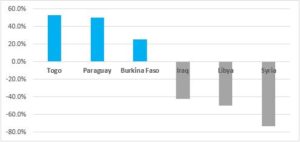

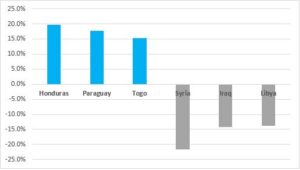

On LGI, Togo, Paraguay and Burkina Faso made the most improvements. Togo increased its score by 52.9%, bringing its rank up by 18 to 114. Paraguay’s score increased by 50.2% and its rank went up by 23 to 91. Burkina Faso’s score improved by 25.2% and its rank by 11, which brought it to number 97t. On the other end, Syria, Libya and Iraq saw major declines in their scores of 73.5%, 50% and 42.5%, respectively. Syria’s ranking saw a major hit with a decrease of 79, while Libya and Iraq’s ranks decreased by 11 and 15, respectively.

Figure 2: Economic Islamicity – Major Score Changes

Figure 3: Legal and Governance Islamicity – Major Score Changes Niger, Honduras and Mali made the highest improvements on the HPRI. Niger improved its score by 52.3% and its ranking jumped from 147 to 135. Honduras improved its score by 37.9% and its rank increased from 95 to 68. And Mali improved by 29.9%, bringing its rank to 137 from 142. Noteworthy declines were made by Syria (-46.2%), Iraq (18.5%) and Saudi Arabia (-15.0%). Their ranks deteriorated by 47, 11 and 18, respectively.

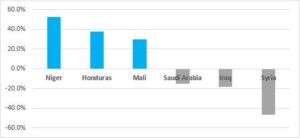

Niger, Honduras and Mali made the highest improvements on the HPRI. Niger improved its score by 52.3% and its ranking jumped from 147 to 135. Honduras improved its score by 37.9% and its rank increased from 95 to 68. And Mali improved by 29.9%, bringing its rank to 137 from 142. Noteworthy declines were made by Syria (-46.2%), Iraq (18.5%) and Saudi Arabia (-15.0%). Their ranks deteriorated by 47, 11 and 18, respectively.

Figure 4: Human and Political Rights Islamicity – Major Score Changes On the IRI, top performers included Libya with a score increase of 21.2%, Armenia with an increase of 18.4% and Burkina Faso with an increase of 10.0%. Their ranks improved by 27, 6 and 9, respectively. Major declines were seen by Syria with a decrease of 72.4%, Saudi Arabia with a 24.7% decrease and the Dominican Republic with a 14.2% decrease. Their ranks suffered correspondingly with a decrease of 41, 21 and 19, respectively.

On the IRI, top performers included Libya with a score increase of 21.2%, Armenia with an increase of 18.4% and Burkina Faso with an increase of 10.0%. Their ranks improved by 27, 6 and 9, respectively. Major declines were seen by Syria with a decrease of 72.4%, Saudi Arabia with a 24.7% decrease and the Dominican Republic with a 14.2% decrease. Their ranks suffered correspondingly with a decrease of 41, 21 and 19, respectively.

Figure 5: International Relations Islamicity – Major Score Changes Lastly, on the aggregate level, noteworthy improvements were made by Honduras, Paraguay and Togo. Honduras increased its score by 19.8% and its ranking by 20. Paraguay’s score increased by 17.7% and rank by 14. And Togo improved its score by 15.4% and rank by 15. Syria, Iraq and Libya were the worst performers with declines of 21.6%, 14.2% and 13.8%, respectively. Their rankings also suffered: Syria’s declined by 8, Iraq’s by 10 and Libya’s by 8.

Lastly, on the aggregate level, noteworthy improvements were made by Honduras, Paraguay and Togo. Honduras increased its score by 19.8% and its ranking by 20. Paraguay’s score increased by 17.7% and rank by 14. And Togo improved its score by 15.4% and rank by 15. Syria, Iraq and Libya were the worst performers with declines of 21.6%, 14.2% and 13.8%, respectively. Their rankings also suffered: Syria’s declined by 8, Iraq’s by 10 and Libya’s by 8.

Figure 6: Overall Islamicity – Major Score Changes

3 Focus on Muslim Countries

In 2017, there were 39 countries for which we had adequate data that were either self-declared Islamic republics or had governments that had adopted Islam as the official state religion, or where Islam was the country’s primary religion, or where the country had a significant Muslim population.[5] In the Islamicity Indices, we investigated 152 countries, which had been additionally broken into various sub-categories of countries for a more nuanced comparison: High, Upper-Middle, Lower-Middle and Low Income Countries, OECD Countries, Non-OECD Countries, Persian Gulf Countries, OIC Countries and Non-OECD Non-OIC Countries.

In this chapter, we compare the results of those countries and evaluate their performance along all five Islamicity Indices, starting with the overall scores.

3.1 Overall Islamicity

Starting with an assessment of the countries’ overall performance in 2017, we look at the sub-categories of the countries and their average rankings. It is no surprise that the OECD and high-income countries performed best with a median ranking of 21 and 28, respectively. They were followed by the upper middle income, non-OECD and non-OIC, lower middle income, and non-OECD. The OIC countries, on average ranked 108th, which falls in the third quartile and slightly above the fourth. Only the low-income countries fared worse.

Table 4: Average Islamicity Rankings for Categories of Countries

| Average Rankings | OI | EI | LGI | HPRI | IRI |

| All Countries (152) | 76 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 76 |

| OECD | 21 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 37 |

| High Income | 28 | 29 | 27 | 31 | 49 |

| Upper Middle Income | 79 | 81 | 82 | 76 | 83 |

| Non-OECD Non-OIC | 87 | 91 | 87 | 83 | 80 |

| Lower Middle Income | 103 | 100 | 104 | 102 | 90 |

| Non-OECD | 94 | 93 | 93 | 94 | 88 |

| OIC | 108 | 98 | 105 | 115 | 106 |

| Low Income | 124 | 123 | 122 | 124 | 95 |

Looking at the scores, significant improvements in overall scores are made by Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali, increasing their scores by 12.39%, 11.60% and 10.36%, respectively. Significant declines were made by Syria (-21.58%), Iraq (-14.23%) and Libya (-13.76%).

Burkina Faso’s overall score improved from 3.47 to 3.90. The country has been seeing major new developments since the authoritarian regime that had been in place for more than a quarter of a century was finally ousted in October 2014 in what the locals call the “popular insurrection.” November and December 2015 marked the elections of a new national assembly and government and the beginning of the making of a new Burking Faso.[6]

Niger improved its score from 2.93 to 3.27. In 2016, the country experienced contentious presidential elections. Although there were not any major outbreaks of violence during the electoral process, tension between government and opposition supporters ran high, often taking an ethno-regionalist character.[7] Niger had a more peaceful 2017 that began with the peaceful surrender of 30 local Boko Haram recruits.

Lastly, Mali increased its score from 2.80 to 3.09, despite eruption of violence in the central and northern part of the country, following the collapse of the peace talks between the government and armed groups.

Table 5: Overall Islamicity Index for Muslim Countries

| Country | Rank | Score |

| Malaysia | 43 | 6.22 |

| United Arab Emirates | 47 | 6.02 |

| Albania | 48 | 5.94 |

| Qatar | 51 | 5.84 |

| Oman | 62 | 5.11 |

| Bahrain | 67 | 5.03 |

| Kuwait | 73 | 4.78 |

| Indonesia | 74 | 4.73 |

| Tunisia | 75 | 4.65 |

| Jordan | 77 | 4.62 |

| Senegal | 78 | 4.62 |

| Turkey | 81 | 4.48 |

| Saudi Arabia | 88 | 4.40 |

| Morocco | 93 | 4.18 |

| Burkina Faso | 100 | 3.90 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 101 | 3.89 |

| Azerbaijan | 108 | 3.64 |

| Lebanon | 112 | 3.50 |

| Niger | 116 | 3.27 |

| Sierra Leone | 121 | 3.13 |

| Mali | 123 | 3.09 |

| Tajikistan | 124 | 3.03 |

| Algeria | 125 | 3.01 |

| Bangladesh | 126 | 2.96 |

| Uzbekistan | 128 | 2.90 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 130 | 2.85 |

| Nigeria | 131 | 2.85 |

| Turkmenistan | 132 | 2.82 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 134 | 2.65 |

| Libya | 136 | 2.57 |

| Pakistan | 137 | 2.53 |

| Guinea | 139 | 2.45 |

| Iraq | 141 | 2.41 |

| Mauritania | 142 | 2.25 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 144 | 2.18 |

| Afghanistan | 148 | 1.58 |

| Chad | 150 | 1.55 |

| Sudan | 151 | 1.51 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 152 | 1.10 |

3.2 Economic Islamicity

How Islamic are Muslim countries or what is their degree of economic “Islamicity”? The goals for a prosperous economic system are (i) achievement of economic justice and achievement of sustained economic growth, (ii) broad-based prosperity and job creation and (iii) adoption of sound and consistent economic and financial practices. Toward these ends, the Economic Islamicity Index is based on 20 economic and social variables or proxies or eight areas of fundamental economic principles. Those eight areas are: Economic Opportunity and Economic Freedom; Job Creation and Equal Access to Employment; Property Rights and Sanctity of Contracts; Provisions to Eradicate Poverty, Provision of Aid and Welfare; Supportive Financial System; Adherence to Islamic Finance; Economic Prosperity and Economic Justice.

The results of the Economic Islamicity Index are shown in table below.

Table 5: Economic Islamicity Index for Muslim Countries

| Country | Rank | Score |

| Malaysia | 24 | 7.45 |

| United Arab Emirates | 29 | 7.17 |

| Bahrain | 38 | 6.92 |

| Qatar | 40 | 6.75 |

| Oman | 48 | 6.02 |

| Albania | 52 | 5.78 |

| Kuwait | 53 | 5.71 |

| Jordan | 61 | 5.35 |

| Saudi Arabia | 64 | 5.27 |

| Indonesia | 69 | 5.07 |

| Azerbaijan | 77 | 4.71 |

| Turkey | 82 | 4.57 |

| Morocco | 84 | 4.51 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 87 | 4.46 |

| Iraq | 90 | 4.20 |

| Burkina Faso | 92 | 4.17 |

| Lebanon | 98 | 4.06 |

| Senegal | 103 | 3.88 |

| Tunisia | 105 | 3.85 |

| Pakistan | 107 | 3.80 |

| Turkmenistan | 108 | 3.72 |

| Uzbekistan | 109 | 3.71 |

| Niger | 110 | 3.69 |

| Mali | 113 | 3.56 |

| Bangladesh | 114 | 3.55 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 117 | 3.26 |

| Tajikistan | 119 | 3.18 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 122 | 3.08 |

| Nigeria | 123 | 3.07 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 124 | 3.06 |

| Algeria | 129 | 2.98 |

| Sierra Leone | 131 | 2.87 |

| Mauritania | 132 | 2.81 |

| Guinea | 133 | 2.72 |

| Chad | 139 | 2.55 |

| Libya | 142 | 2.45 |

| Afghanistan | 146 | 2.08 |

| Sudan | 149 | 1.85 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 152 | 1.52 |

Looking at the scores, it is not surprising to see Malaysia, the UAE, Bahrain, Qatar and Oman performing well. Aside from Malaysia, the other countries are known to have a natural resource-based economy. Together with them, a total of 10 out of 39 countries (25.6%) have a score of above 5 and have outperformed the median world score. The highest ranked OIC country is Malaysia, which ranked 24th, followed by the UAE at 29, Bahrain at 38, Qatar at 40 and Oman at 48. Their collective average rank was 98, among the lowest in the world. It is noteworthy that with the exception of Malaysia, the other four Muslim countries have small populations and access to oil and gas resources.

The bottom five performers are Chad, Libya, Afghanistan, Sudan and Yemen. Their rank is in the bottom 8%. All five countries are struggling with conflict and internal instability that prevents them from improving economically. Their rankings are some of the lowest in the world.

When compared to OECD countries, the disparities are even more pronounced, where the average ranking is 22.6 and the average score is 7.55. However, even when compared to non-OECD and Middle-Income countries, the Muslim countries still do not perform as well (see the Average Rankings for Five Islamicity Indices above). The Islamic countries fare slightly better than Lower Middle-Income countries, where the average ranking is 100, and significantly better than Low Income countries, which have an average ranking of 123.

The Economic Islamicity Index results indicate there is much left to be desired in the promotion of economic institutions, free markets and good economic governance in Islamic countries.

3.3 Legal and Governance Islamicity

The Legal and Governance Islamicity Index is based on five fundamental areas of legal and governance principles and on 12 variables or proxies. The five areas are: Legal Integrity; Prevention of Corruption; Safety and Security Index; Management Index and Governance and Government Effectiveness. Here, the aim is to measure the prevalence of corruption, the security of property rights, voice and accountability, the rule of law and the effectiveness of governance structures.

The top five performers are the UAE, Qatar, Malaysia, Oman and Albania. Nine out of 39 countries had a score of higher than 5, while a third of them had a score higher than the world median. The OIC countries’ average ranking is 105 and their average score is 3.32. The results are lower in the Legal and Governance Index when compared to Economic Islamicity.

Table 6: Legal and Governance Islamicity Index for Muslim Countries

| Country | Rank | Score |

| United Arab Emirates | 40 | 7.10 |

| Qatar | 43 | 7.05 |

| Malaysia | 49 | 6.34 |

| Oman | 53 | 5.96 |

| Albania | 58 | 5.55 |

| Jordan | 61 | 5.35 |

| Morocco | 64 | 5.14 |

| Kuwait | 65 | 5.10 |

| Saudi Arabia | 66 | 5.05 |

| Bahrain | 68 | 4.99 |

| Tunisia | 69 | 4.98 |

| Senegal | 70 | 4.97 |

| Indonesia | 75 | 4.81 |

| Turkey | 81 | 4.42 |

| Burkina Faso | 97 | 3.72 |

| Azerbaijan | 98 | 3.68 |

| Algeria | 107 | 3.02 |

| Niger | 115 | 2.88 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 118 | 2.79 |

| Lebanon | 118 | 2.79 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 120 | 2.76 |

| Mali | 122 | 2.65 |

| Sierra Leone | 124 | 2.57 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 125 | 2.54 |

| Tajikistan | 129 | 2.27 |

| Turkmenistan | 130 | 2.25 |

| Guinea | 132 | 2.14 |

| Uzbekistan | 133 | 2.09 |

| Bangladesh | 134 | 2.09 |

| Mauritania | 135 | 2.01 |

| Pakistan | 136 | 1.76 |

| Nigeria | 137 | 1.62 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 138 | 1.50 |

| Iraq | 144 | 1.23 |

| Afghanistan | 146 | 1.18 |

| Chad | 148 | 0.87 |

| Sudan | 149 | 0.87 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 150 | 0.83 |

| Libya | 151 | 0.66 |

The bottom five performers are Afghanistan, Chad, Sudan, Yemen and Libya – the same five countries with the lowest EI score. Here, their ranks are in the lowest 5%. These countries have a weak rule of law and fragile political order due to years of conflict or authoritarian regimes.

The results highlight the Muslim countries’ poor performance. Comparing them to the OECD countries, their results are even more pronounced. The OECD’s average ranking is 21. Even when compared to non-OECD and middle-income countries, the OIC results fall short. Here, the Muslim countries’ results are lower than lower middle-income countries, faring better than only the low-income countries. The majority of OIC countries seem to have low level of governance quality and weak rule of law systems as well as high prevalence of corruption. These results are indicative of weak governance institutions, especially the rule of law that is arguably the critical institution for good performance.

3.4 Human and Political Rights Islamicity

The Human and Political Rights Islamicity Index measures 15 variables of human development, civil and political rights and social wellbeing, aggregated along eight fundamental areas of Human Development; Social Capital; Personal Freedom; Civil and Political Rights; Women’s Rights; Access to Education; Access to Healthcare and Level of Democracy.

According to these indicators, Albania, Malaysia, Tunisia, Senegal and Turkey are the top five performers. However, only three of them had a score higher than 5 or performed better than the world median score.

Table 7: Human and Political Rights Islamicity Index for Muslim Countries

| Country | Rank | Score |

| Albania | 52 | 5.89 |

| Malaysia | 71 | 5.00 |

| Tunisia | 71 | 5.00 |

| Senegal | 78 | 4.62 |

| Turkey | 79 | 4.53 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 84 | 4.34 |

| United Arab Emirates | 85 | 4.32 |

| Qatar | 87 | 4.27 |

| Oman | 91 | 4.12 |

| Indonesia | 92 | 4.10 |

| Kuwait | 94 | 4.00 |

| Bahrain | 101 | 3.76 |

| Lebanon | 103 | 3.70 |

| Algeria | 108 | 3.45 |

| Jordan | 109 | 3.43 |

| Saudi Arabia | 110 | 3.40 |

| Libya | 111 | 3.39 |

| Sierra Leone | 112 | 3.20 |

| Uzbekistan | 115 | 3.13 |

| Burkina Faso | 118 | 3.11 |

| Tajikistan | 120 | 3.09 |

| Morocco | 122 | 3.05 |

| Azerbaijan | 123 | 2.99 |

| Turkmenistan | 130 | 2.78 |

| Nigeria | 131 | 2.73 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 132 | 2.71 |

| Bangladesh | 133 | 2.68 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 134 | 2.65 |

| Niger | 135 | 2.59 |

| Mali | 137 | 2.43 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 139 | 2.15 |

| Iraq | 140 | 2.11 |

| Guinea | 141 | 2.01 |

| Pakistan | 142 | 1.96 |

| Mauritania | 144 | 1.89 |

| Sudan | 147 | 1.76 |

| Afghanistan | 150 | 1.36 |

| Chad | 151 | 1.06 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 152 | 0.78 |

The bottom five performers are Mauritania, Sudan, Afghanistan, Chad and Yemen. They rank in the bottom 5%. They are the same lowest performers, barring Mauritania, which has been struggling to reform and democratize after two coups in 2005 and 2008.

As noted earlier, while the OIC countries improved their HPR performance this year, their median score is almost half that of the world. Their average rank is 115, and their score is 3.16. The ranking and score are closer to the results of Low Income countries than to any other group. Here, even the star countries that performed well in EI and LGI fare far worse. Malaysia performs significantly worse here. Except for Albania, other OIC countries fare no better.

3.5 International Relations Islamicity

Last but not least, the International Relations Islamicity, which measures the two core areas of Globalization and Militarization, has been faring similar to the other four main indices. The average ranking and score for the Muslim countries are 106 and 3.71, respectively.

The top five performers in IRI include Albania, Nigeria, Libya, Burkina Faso and Malaysia. Eleven countries (28%) had a score higher than 5 and the median world score. The bottom five performers are Sudan, Yemen, Iran, Iraq and Syria. They fall in the bottom 4%.

Table 8: International Relations Islamicity Index for Muslim Countries

| Country | Rank | Score |

| Albania | 12 | 7.73 |

| Nigeria | 40 | 6.22 |

| Libya | 40 | 6.22 |

| Burkina Faso | 46 | 6.02 |

| Malaysia | 48 | 5.82 |

| Senegal | 51 | 5.76 |

| Sierra Leone | 59 | 5.39 |

| Indonesia | 62 | 5.36 |

| Niger | 71 | 5.16 |

| Tunisia | 74 | 5.07 |

| Mali | 76 | 5.00 |

| Tajikistan | 85 | 4.67 |

| Bangladesh | 88 | 4.64 |

| United Arab Emirates | 95 | 4.38 |

| Turkey | 96 | 4.31 |

| Qatar | 102 | 4.14 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 104 | 4.11 |

| Guinea | 111 | 3.91 |

| Jordan | 114 | 3.82 |

| Morocco | 116 | 3.65 |

| Lebanon | 120 | 3.42 |

| Kuwait | 122 | 3.36 |

| Bahrain | 124 | 3.22 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 128 | 3.06 |

| Saudi Arabia | 132 | 2.86 |

| Oman | 134 | 2.80 |

| Pakistan | 135 | 2.76 |

| Mauritania | 139 | 2.34 |

| Azerbaijan | 140 | 2.20 |

| Uzbekistan | 140 | 2.20 |

| Chad | 143 | 2.07 |

| Turkmenistan | 144 | 1.97 |

| Afghanistan | 145 | 1.88 |

| Algeria | 146 | 1.71 |

| Sudan | 146 | 1.71 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 148 | 1.61 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 149 | 1.61 |

| Iraq | 151 | 1.48 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 152 | 1.05 |

The results for the Muslim countries in this index are the worst among all groups of countries measured. Their ranking is far lower than even that of the low-income countries. The results indicate that Muslim countries are less open to globalization and more prone to militarization and wars. The two – globalization and militarization – go hand in hand. As counties become engaged in conflict, they become less open. Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen and Iraq suffer from wars, while many others suffer from internal conflict and terrorism, preventing them from engaging in global exchange.

4 Focus on Muslim Countries by Region

4.1 Africa (North, Western, and Central African countries)

In 2017, the African Muslim countries averaged a rank of 101 in OI. They performed in the low 100s along EI, LGI, HPRI and IRI. Their performance was worst in LGI and best in International Relations. The central African countries performed least well, while the western African countries did relatively better among the group

Table 9: Muslim African Countries Islamicity Indices

| Country | EI | LGI | HPRI | IRI | OI |

| Senegal | 93 | 76 | 82 | 65 | 79 |

| Tunisia | 94 | 76 | 76 | 75 | 80 |

| Burkina Faso | 89 | 96 | 105 | 61 | 87 |

| Morocco | 83 | 74 | 106 | 97 | 90 |

| Niger | 96 | 108 | 113 | 74 | 98 |

| Sierra Leone | 108 | 113 | 103 | 70 | 99 |

| Mali | 98 | 112 | 115 | 76 | 100 |

| Nigeria | 105 | 127 | 111 | 58 | 100 |

| Libya | 115 | 142 | 100 | 58 | 104 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 105 | 110 | 112 | 106 | 108 |

| Algeria | 107 | 106 | 100 | 126 | 110 |

| Guinea | 111 | 119 | 122 | 93 | 111 |

| Chad | 113 | 139 | 136 | 121 | 127 |

| Sudan | 124 | 139 | 125 | 126 | 128 |

| Africa | 103 | 110 | 107 | 86 | 101 |

4.2 Asia (Asia-Pacific, South Asia, and Central Asia)

The Asian Muslim countries also did not fare much better than their African counterparts. Their average OI rank was 100, performing best in EI and worst in LGI. The Asia-Pacific countries ranked best, while the South and Central Asian countries lagged far behind.

Table 10: Muslim Asian Countries Islamicity Indices

| Country | EI | LGI | HPRI | IRI | OI |

| Malaysia | 39 | 56 | 76 | 64 | 58 |

| Indonesia | 75 | 79 | 90 | 71 | 79 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 84 | 110 | 86 | 90 | 92 |

| Azerbaijan | 80 | 96 | 107 | 119 | 100 |

| Tajikistan | 104 | 118 | 105 | 81 | 102 |

| Bangladesh | 98 | 120 | 111 | 82 | 103 |

| Uzbekistan | 96 | 120 | 105 | 119 | 110 |

| Turkmenistan | 96 | 118 | 110 | 122 | 111 |

| Pakistan | 94 | 125 | 122 | 110 | 113 |

| Afghanistan | 120 | 134 | 131 | 124 | 127 |

| Asia | 89 | 108 | 104 | 98 | 100 |

4.3 Middle East

The Middle Eastern countries fared better than their African and the rest of Asia counterparts. Their average OI rank was 95, performing best in EI and least well in IRI. The UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Oman led the group; while the instabilities in Iraq, Syria and Yemen as well as international sanctions imposed on Iran resulted in lower performance levels.

Table 11: Muslim Middle Eastern Countries Islamicity Indices

| Country | EI | LGI | HPRI | IRI | OI |

| United Arab Emirates | 43 | 44 | 86 | 86 | 65 |

| Qatar | 49 | 45 | 87 | 89 | 68 |

| Bahrain | 47 | 76 | 95 | 103 | 80 |

| Oman | 60 | 61 | 89 | 110 | 80 |

| Kuwait | 65 | 74 | 91 | 101 | 83 |

| Jordan | 71 | 71 | 100 | 94 | 84 |

| Saudi Arabia | 72 | 75 | 100 | 109 | 89 |

| Lebanon | 90 | 110 | 96 | 100 | 99 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 105 | 113 | 111 | 128 | 114 |

| Iraq | 88 | 133 | 120 | 130 | 118 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 102 | 129 | 119 | 136 | 122 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 129 | 139 | 140 | 128 | 134 |

| Middle East | 77 | 89 | 103 | 109 | 95 |

4.4 Europe

Europe fared the best among the four groups. It averaged 70th rank in OI, performing best in IRI, and least well in LGI. Albania led the group while issues in Turkey resulted in lower performance levels.

Table 12: Muslim European Countries Islamicity Indices

| Country | EI | LGI | HPRI | IRI | Overall |

| Albania | 64 | 68 | 63 | 35 | 57 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 69 | 93 | 66 | 50 | 69 |

| Turkey | 83 | 85 | 83 | 87 | 84 |

| Europe | 72 | 82 | 71 | 57 | 70 |

5 Summary and Recommendations

Given our results, one can surmise that the lack of economic, financial, political, legal and social development can be attributed to the age-old problems of developing countries, such as inefficient institutions, especially the rule of law, a pervasive culture of corruption, inconsistent and shortsighted economic policies, limited and inequitable opportunities for individual development and growth, injustice, the absence of freedom, little respect for human and political rights, strife and armed conflicts and other traditional shortcomings of most developing country.

It is, in fact, the shortcomings of the governments and their respective policies, not religion, that account for the dismal economic, financial, political, legal and social developments and progress in the majority of OIC countries (even those blessed with oil). This is further reinforced by the Islamic economic, financial, political, legal and social principles represented by 47 proxies used in the Islamicity Indices and the result that the countries of Northern Europe, New Zealand, Australia and Canada are the countries that perform the best based on Islamicity Indices. In fact, the recommended institutions, though different than the recommendations of Adam Smith and institutionalists, share many common characteristics; a major difference being Islam’s emphasis on justice, equality and caring for those who are unable to take care of themselves. If examined closely, all 47 proxies of the Index are standard practices of good governance and good economic, financial, political, legal and social policies, applicable to any country regardless of religious orientation. Measuring countries’ respect for human rights and freedom, social and economic justice, hard work, equal opportunity for all to develop, the absence of corruption, absence of waste and hoarding, ethical business practices, well-functioning markets and a legitimate political authority should naturally result in flourishing economies. It is evident in our results that these teachings, not the actual practice of those that are labeled Muslim, should be the basis for judging a society’s pretensions to Islamicity.

Our preliminary results show that Muslim countries are not as Islamic in their practice as one might expect; instead, most developed countries tend to place higher on our Islamicity Indices. As Mohammad Abduh clearly observed over a century ago, “I went to the West and saw Islam, but no Muslims; I got back to the East and saw Muslims, but not Islam.” Along the distinct indices, the Islamic countries performed best in EI (Economic Islamicity Index)and worst in LGI (Legal and Governance Islamicity Index). Although the countries have improved their LGI performance and ranking, there is still a long way to go to at least do as well as the non-Islamic countries. Economically, the countries’ scores deteriorated as did human and political rights and international relations scores.

The countries that best exhibit the teachings of Islam show a strong performance in all dimensions and demonstrate stability in nearly all their performance indicators over time. Simply said, successful countries cannot fail in a few dimensions and expect to succeed. Humans need freedom, good opportunities and an environment with manageable exposure to risk to thrive. At the same time, when we look back on the movement in the indices since 2000 we see that successful countries exhibit stability year after year in most, if not all, of the many inputs that make up each index. They have strong institutions that are essential for economic and social development and growth. This is in contrast to the performance of Muslim countries, countries that profess Islam but do not reflect the teachings of the Qur’an that are the underlying basis for the Islamicity Indices. Their performance has been sub-par. The results lead to one inescapable conclusion—Muslim countries have little choice but to adopt effective institutional reform and scaffolding as recommended in Islam—recommendations that are upheld outside of Islam. Muslim countries need essential political reforms and a realistic timetable for transitioning to representative and accountable governments.

Our country partners plan to publicize the underlying basis of the Islamicity Indices Program to the general public in order to solicit local and widespread support for this important initiative—for Muslims to take ownership of their religion and to work for peaceful reform The latest results of the indices will be publicized in each partner country as well as more broadly on social media. We hope that in time we will build an international community of Muslims who better understand the message of their religion from the Qur’an and work toward peaceful reform and effective institutions in their own countries while affording active support to those in all Muslim countries. This is a journey that will take time because of centuries of missteps and abuse but it is a journey that must start on a solid footing to build effective institutions and initiate much-needed reform. Simultaneously, we believe that Islamicity Indices will be a simple and persuasive method of transmitting the message of Islam—justice and peace— and its practice to non-Muslims in order to enhance global relations.

6 Islamicity Foundation

The Islamicity Foundation is incorporated as a tax-exempt organization in the U.S. state of Maryland. Although the Islamicity Foundation has been organized as a stand-alone entity, in time and, if appropriate, it could partner with a world-class university. This would afford the Foundation and its mission more visibility; it would facilitate fundraising activities; and most important, by teaching seminars on Islam and development and on Islamicity Indices, the Foundation could develop a cadre of young collaborators to better accomplish its mission around the world.

6.1 Board of Advisors

The Foundation’s Advisory Board will guide the foundation toward achieving its mission to build effective institutions and sustain reform in Muslim countries. We hope eventually to establish a Board of 12-15 eminent women and men, with diverse professional and regional backgrounds, to afford the Foundation and the Islamicity Project a broad perspective on the process of institution building and reform across the Muslim World. Because we may eventually merge the Foundation into a world-class university, we plan to keep a number of these board membership positions open to invite a few distinguished alumni of the partner university to join the Board.

We are proud to announce the first three members of our Advisory Board: (Advisory Board)

Dr. Ali A. Allawi was born in Iraq and educated in England and the United States where he earned a BS in civil engineering from MIT in 1968 and an MBA from Harvard University in 1971. Dr. Allawi was a leader in the Iraqi exile community in London during the rule of Saddam Hussein and lives in London and Baghdad. Allawi has enjoyed four distinct careers. As a businessman, he was a highly successful merchant banker in London. As an academic, he was a professor at Oxford University, a senior visiting fellow at Princeton University and research professor at the National University of Singapore. As a politician, he was appointed Iraq’s Minister of Trade in 2003, its first post-war civilian Minister of Defense in 2004 and in 2005 he was appointed Minister of Finance. As a celebrated author, his books are (i) The Occupation of Iraq, (ii) The Crisis of Islamic Civilization and (iii) Faisal I of Iraq. The Times Book Review called The Occupation of Iraq “ . . . the most comprehensive historical account of the disastrous aftermath of the American Invasion.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy awarded The Crisis of Islamic Civilization the Silver Prize in its annual book awards in 2009, while The Economist named the book one of the Best Books of 2009. He was number four in Prospect Magazine’s 2013 World Thinkers Poll for his insight on the history and future direction of Islamic Society.

Dr. Ali A. Allawi was born in Iraq and educated in England and the United States where he earned a BS in civil engineering from MIT in 1968 and an MBA from Harvard University in 1971. Dr. Allawi was a leader in the Iraqi exile community in London during the rule of Saddam Hussein and lives in London and Baghdad. Allawi has enjoyed four distinct careers. As a businessman, he was a highly successful merchant banker in London. As an academic, he was a professor at Oxford University, a senior visiting fellow at Princeton University and research professor at the National University of Singapore. As a politician, he was appointed Iraq’s Minister of Trade in 2003, its first post-war civilian Minister of Defense in 2004 and in 2005 he was appointed Minister of Finance. As a celebrated author, his books are (i) The Occupation of Iraq, (ii) The Crisis of Islamic Civilization and (iii) Faisal I of Iraq. The Times Book Review called The Occupation of Iraq “ . . . the most comprehensive historical account of the disastrous aftermath of the American Invasion.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy awarded The Crisis of Islamic Civilization the Silver Prize in its annual book awards in 2009, while The Economist named the book one of the Best Books of 2009. He was number four in Prospect Magazine’s 2013 World Thinkers Poll for his insight on the history and future direction of Islamic Society.

Dr. Abbas Mirakhor was born in Iran and received his BA, MA and PhD in economics from Kansas State University. Dr. Mirakhor has enjoyed two outstanding careers. He was an economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where he later served as its Executive Director and in 2008 he retired as the Dean of its Executive Board (its effective day-to-day governing body); while on the Board, Mirakhor became arguably its most respected Director. His other career has been in academics, where he continues to flourish. He has been a pioneer and the leading global figure in Islamic finance over the last two decades. He has taught at a number of universities in Iran and the United States and most recently in Malaysia where he was the First Holder of the INCEIF Chair in Islamic Finance. Mirakhor has received a number of national awards and the Islamic Development Bank’s Prize for Research into Islamic economics. He is the author of dozens of academic books and hundreds of research articles and conference presentations. His talks and lectures have been the inspiration of the Islamicity Indices project and two of his books on development in Islam and the ideal Islamic economic system and a forthcoming book on justice have provided the project’s foundation. He now resides in the United States.

Dr. Jomo Kwame Sundaram was born in Penang, Malaysia. He studied at the Penang Free School, Royal Military College, Yale (BA) and Harvard (MPA, PhD). Dr. Sundaram has taught at USM, Harvard, Yale, UKM, UM and Cornell; he has served as a Visiting Fellow at Cambridge University, as a Senior Research Fellow at the National University of Singapore, and was the Third Holder of the Tun Hussein Onn Chair in International Studies at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. Currently, he is a Visiting Senior Fellow at Khazanah Research Institute, Visiting Fellow at the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Columbia University, and Adjunct Professor at the International Islamic University in Malaysia. He has authored and edited over a hundred books. In parallel with his distinguished academic career, he has been an international and national public servant of great renown. He was the United Nations Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs from 2005 until 2012, Research Coordinator for the G24 Intergovernmental Group on International Monetary Affairs and Development, and Assistant Director General for Economic and Social Development, Food and Agriculture Organization. He served as adviser to the President of the Sixty-third United Nations General Assembly and as a member of the Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System. He was G20 Sherpa to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki- moon, and also UN G20 Finance Deputy. He received the 2007 Wassily Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought.

Dr. Jomo Kwame Sundaram was born in Penang, Malaysia. He studied at the Penang Free School, Royal Military College, Yale (BA) and Harvard (MPA, PhD). Dr. Sundaram has taught at USM, Harvard, Yale, UKM, UM and Cornell; he has served as a Visiting Fellow at Cambridge University, as a Senior Research Fellow at the National University of Singapore, and was the Third Holder of the Tun Hussein Onn Chair in International Studies at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. Currently, he is a Visiting Senior Fellow at Khazanah Research Institute, Visiting Fellow at the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Columbia University, and Adjunct Professor at the International Islamic University in Malaysia. He has authored and edited over a hundred books. In parallel with his distinguished academic career, he has been an international and national public servant of great renown. He was the United Nations Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs from 2005 until 2012, Research Coordinator for the G24 Intergovernmental Group on International Monetary Affairs and Development, and Assistant Director General for Economic and Social Development, Food and Agriculture Organization. He served as adviser to the President of the Sixty-third United Nations General Assembly and as a member of the Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System. He was G20 Sherpa to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki- moon, and also UN G20 Finance Deputy. He received the 2007 Wassily Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought.

6.2 Board of Directors

Hossein Askari: President

Hossein Mohammadkhan: Vice-President

Fara Abbas

Anna Askari: Secretary-Treasurer

6.3 Webmaster

Mostafa Omidi

7 Appendix: Country Partners

Country partners are critical for the success of our mission. These individuals and future partner institutions will represent a global community who understand the mission of Islamicity and who will work together for needed reforms in Muslim-majority countries. The country partners will join hand-in-hand to support each other, across countries, to build effective institutions in the quest for better lives. In time, we plan to have partners in all Muslim-majority countries and even in some non-Muslim-majority countries who want to support the process of institution building and reform in Muslim countries.

Our country partners are:

Afghanistan: Fara Abbas

Bangladesh: Hasina Khanom

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Edib Smolo

Indonesia: Dr. Putri Swastika

Iran: Hossein Mohammadkhan

Malaysia: Dr. Liza Mydin and Daud Vicary Abdullah

Nigeria: Dr. Fatima Muhammad Abdulkarim

Pakistan: Dr. Irum Saba

Senegal: Dr. Adama Dieye

Singapore: Dr. Hazik Mohamed

Tunisia: Dr. Khaled Troudi

Turkey: Dr. Nihat Gumus

Fara Abbas:

Education: BBA, Finance, School of Business, and Minor in International Affairs, Elliot School of International Affairs, George Washington University, Washington DC; MA, International Policy Studies, Stanford University, California.

Current Position: Consultant on economic development

Previous Positions: Advisor to senior government officials in Afghanistan

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “To help strengthen public institutions and economically develop the Muslim world so they can become active contributors to the peace and prosperity of the global community of nations.”

Hasina Khanom:

Education: BSc, Economics/Mathematics, University of Akron; MSc, Engineering and Applied Statistics, Rochester Institute of Technology; MBA, Statistics and Economics, Rochester Institute of Technology.

Current Position: Associate Director/Senior Research Analyst for Survey and Institutional Research, the University of Pennsylvania

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “I am a self-defined outcome-oriented person, and have always found it necessary to not only engage in social critique but to develop creative solutions to the well-known problems facing our global village today. As such, I find the Index to be a platform out of which reformative policies can be developed which have the potential to directly improve the lived realities of people in Muslim societies. My experiences in institutional research and effectiveness aligns neatly with this project’s own aims to strengthen civil institutions, which are ultimately the backbone of a robust civil society.”

Edib Smolo:

Education: BSc and MSc, Economics, International Islamic University, Malaysia; PhD Candidate, Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia.

Current Position: Consultant in Islamic Finance

Previous Positions: CEO Contact Travel Ltd (Bosnia & Herzegovina), International Islamic Finance Manager TOSAN (Iran), Researcher International Shari’ah Research Academy (ISRA, Malaysia)

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “The Islamic community (the Ummah) is going through difficult times, perhaps the most difficult ones since the Prophet (pbuh) established a community in Madinah. In my humble view, this is due to straying away from Islamic teachings. The Islamicity Foundation is there to identify missing link and help us improve the overall conditions within the Ummah as whole.”

Dr. Putri Swastika:

Education: PhD, Islamic Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia

Current Position: Lecturer at Faculty of Islamic Economics and Business (Islamic National Institute (Institute Agama Islam Negeri) Metro, Lampung, Indonesia

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “It is a call for contributions to the initiative of implementing Islamic institutions in the national policy of the Muslim World.”

Dr. Liza Mydin:

Education: PhD, Islamic Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia;

Visiting Scholar, George Washington University, Washington DC.

Current Position: Head of Research and Advisory at Maybank, Malaysia

Previous Positions: Al Rajhi Bank Malaysia as the Vice President of Compliance and served the bank until 2014 where she provided advisory, review and implementation of regulatory requirements. Conducted post-doctoral research for the Islamicity Index Project.

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “In Malaysia, there is a departure from understanding the meaning the Qur’an and practices of the Prophet in the education system. This has resulted in societal problems and governance related issues in many institutions. I am honored to be a part of this initiative to assess how we can effect change and ensure our society thrives.”

Daud (David Vicary) Abdullah:

Education: BSc, Economic and Social History, University of Bristol, UK.

Current Position: Managing Director of DVA Consulting an Islamic Finance Advisory, Chairman of the Advisory Board to the AIFC (Astana International Financial Centre) and IslamicMarkets.com, Consultant and Advisor to the IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies) and Advisor to INCEIF (International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance).

Previous Positions: President and CEO of INCEIF (the Global University of Islamic Finance with over 2000 students from 85 countries from 2011-2017), Global Head of Islamic Finance for Deloitte, 2009-2011, Acting CEO and COO Asian Finance Bank, 2007-09 and Founding Managing Director of Hong Leong Islamic Bank 2005-09

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “Doing the right thing to promote Islam and Islamic Finance.”

Dr. Fatima Muhammad Abdulkarim:

Education: PhD, Islamic Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia; MBA, University Kebangsaan, Malaysia; BBA (Hons), E-commerce, Infrastructure University, Malaysia.

Current Position: Lecturer at Department of Banking and Finance, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences, Federal University Dutse, Jigawa State, Nigeria

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “I joined this project in order to get an insight of what is happening in Muslim countries. It will entail the acquisition of quantifiable data that will help explain the degree to which Islamic teachings are complied with in running the day-to-day affairs of a country. To help contribute such information through knowledge sharing toward the development of knowledge in such area and to compare and contrast between different countries in how they run their affairs relating to life and how Islam is used as a guide in such running of life and what impact it has on the people.”

Dr. Irum Saba:

Education: PhD, Islamic Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia; PhD, Islamic Banking and Insurance, Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, London, UK; MSc (with distinction), Commerce, INCEIF, Malaysia.

Current Position: Assistant Professor/Program Director MS Islamic Banking and Finance, Institute of Business Administration, Karachi, Pakistan

Previous Positions: Joint Director, State Bank of Pakistan

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “In order to learn and contribute to the foundations of effective institutions in Muslim world.”

Dr. Adama Dieye:

Education: PhD, Islamic Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia; Advanced Diploma in Islamic Finance, BIBF, Bahrain; Doctor of Economic Sciences, University of Auvergne, Clermont Ferrand, France; MSc, Economics, University of Dakar, Senegal; MS in Applied Mathematics, University of Dakar, Senegal.

Current Position: Part time lecturer in Financial programming at Gaston Berger University – Saint Louis/Senegal; Cheikh Anta DIOP University – Dakar/Senegal and Part time lecturer in Islamic Economics and Islamic Finance at the African Center for Higher Studies in Management CESAG –Dakar /Senegal; The Bordeaux Ecole Management- BEM/Dakar

Previous Positions: Adviser to the Minister of Economy and Finance, Government of Senegal and Director of the Administration and Training Department, BCEAO

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “Share my professional experience and skill as contribution to the expansion of Islamic knowledge”

Dr. Hazik Mohamed:

Education: PhD, Islamic Finance, INCEIF, Malaysia; MSc, Finance, Baruch College, New York; BSc, Mechanical Engineering, University of Arkansas, Arkansas.

Current Position: Managing Director of Stellar Consulting Group Pte. Ltd., Singapore, working on blockchain-based innovations and business growth strategies for start-ups

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “The Islamicity Indices provide clear measurable indicators that be used as performance measures on policy effectiveness. It quickly defines what people say against what they actually do. It also provides a broad understanding of the universality of Islamic values which can be exhibited by Muslim as well as non-Muslim institutions.”

Dr. Khaled Troudi:

Education: PhD, Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter, UK; MA, Comparative Religion, Western Michigan University, Michigan; BA, Islamic Studies and Qur’anic Sciences, Islamic University of Medina, Saudi Arabia.

Current Position: Director, Center of Islamic Studies, Zaytuna University, Tunisia

Previous Positions: Assistant Professor and Researcher in Islamic studies, Comparative Religion, and Qurʾanic studies at the center of the Islamic studies/ Kairouan. Zaytuna University. Tunisia; Assistant Professor in Islamic studies and comparative Religion at the Institute of Islamic world studies at Zayed University, UAE; Research Associate and Assistant Professor in Arab and Islamic studies at the International Institute of Islamic Thought, Herndon Virginia, USA.

Hossein Mohammadkhan:

Education: MSc, Finance, George Washington University, Washington DC; BSc, Electrical Engineering, Tehran Azad University, Iran.

Current Position: Business Developer and Consultant, and Socio-Economic Researcher

Past Positions: Business Analyst at a number of companies

Reason for joining the Islamicity Indices Project: “I truly believe we can change the Muslim world in a most peaceful and reasonable way by showing Muslims the inconsistency of where they are today. Islam can benefit the world, but not the way it is currently represented and practiced in most of Muslim countries.”

————

References:

[1] Especially in his book: The Theory of Moral Sentiments

[2] There is no distinction made between Sunni and Shia Muslim countries. Approximately 12-15% of the world’s Muslims are Shia with the largest representation in Iran and Iraq.

[3] For example, United Nations Human Development Index (UNHDI), Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EUI) Democracy Index, Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index (Economic Freedom of the World Index), Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Index, etc.

[4] The results do not reflect most recent developments in countries because the information (especially available indices) are largely based on 2016 data. This time lag in available indices, in turn, results in a lag in the incorporation of most recent developments in the Islamicity Indices.

[5] See Table 4

[6] See Table 4

[7] https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2017/niger